A Tale of A Thousand Buildings: The Work of Ricardo Bofill

Title: A Tale of A Thousand Buildings: The Work of Ricardo Bofill

Authors: Aragüez

Keywords: Architecture, Bofill, Spain, Urbanism, Interview

1 INTRODUCTION

Ricardo Bofill defines himself as a humanist, a renaissance man, a singular architect detached from the ‘Star System’ –yet inevitably belonging to it. With an impressively prolific international career, spanning from airport terminals to governmental buildings to headquarters of global corporations and social housing, he definitely stands out among the very few Spanish architects whose production overseas excels the one accomplished in Iberian grounds. With his office Taller de Arquitectura, hosted in an old cement factory in the outskirts of Barcelona, his architectural production has been equally admired and despised, praised at times for its morphological complexity as much as discredited for its classical formalism.

Our online conversation is paced by the lighting up and burning out of the cigarettes that Ricardo, now past 80, smokes with almost no break. Sharp in his replies, eloquent, well versed, and extremely confident of his own truth, the discussion jumps from contexts as far as Japan, France and Catalunya through the buildings materialised in each place. We talk about building in context from the periphery of Europe; the failure of Postmodernism and its misconceptions; and the importance of the preservation of urban identities and cityscapes for a Mediterranean architect. With a chameleonic career that has adapted to the trends and powers of each time, Taller de Arquitectura works today on the outline of entire cities in China: what would come next?

2 PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY

Ricardo Bofill: Photo by Silvia T. Colmenero

Perhaps due to professional deformation, in some way your architectural trajectory reminds me of the line that Arata Isozaki has followed: changing his styles, eclectic in his references, and global in his practice, differentiating yourself from other Spanish architects of his time as Isozaki differentiates himself from his Japanese contemporaries. I imagine you know Isozaki well, and I would like to know what you think about this parallelism.

Yes, Isozaki is a good friend of mine, we’ve had a good relationship and talked a lot about architecture. I quite like what he does; he is a particular case in Japan, since he has worked relatively little there and has done many projects abroad. He is what I call a “nomadic architect”, who like me has been traveling around the world for a long time. And yes, I am equally an atypical architect with respect to the “star system” of architecture since ever, from the beginning until now.

Nowadays I am able to make entire cities. In China as well as in other countries we get commissions for urban design and this is the background against which I work. As for the vocabulary, I’ve been changing it because this is what I really like. It would bore me to do the same thing all my life, the way other great architects like Richard Meier and others have done. I think that architecture must be changed according to the place, to its genius loci. The architecture you do in Tokyo will not be the same as the one you do in New York, Africa, or Barcelona. These differences have somehow led me to do research on the vocabulary of architecture and to change it throughout my life. I like projects to be different. I am very critical of my own projects and this criticism also helps me to change my architecture. Anyway, when you have been doing architecture for so many years, you always have a background present in every project. From this point of view, I am a nomad architect, as they called me in France in the 60s, because I have traveled a lot and I have built on 35 cities. I have done more than a thousand projects.

Many more projects than the average of all the architects of your time, and many more than Isozaki certainly.

Not all of those projects have been built, of course, but I have built in 35 different cities in different parts of the world.

La Place du Nombre d’Or, Antigone, Montpellier France: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Place du Nombre d’Or, Antigone, Montpellier France: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Place du Nombre d’Or, Antigone, Montpellier France: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Place du Nombre d’Or, Antigone, Montpellier France: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Your building for Shiseido fits like a glove in Ginza, and yet it has something Mediterranean about it. Do you think you have acquired this ability to blend in overtime? Your buildings from the 80s had a more decontextualized language.

Yes, I am a Mediterranean architect. The Mediterranean is about the culture of the streets, the squares, the gardens, urban continuity, public space, it’s the culture that surrounds me. Ginza was a project that I was commissioned to do directly from the Shisheido presidency. They had a very small and expensive plot of land, in a neighborhood that could be compared to Gracia in Barcelona. Ginza is a very particular, very lively, and important neighborhood in Tokyo. There, we made a vertical element, and I can say that with the Japanese you can work with that space and emptiness because they understand it well. It’s not like that in China. The Japanese leave empty spaces and have a sense of space, which for me is the proper sense of architecture. The structure of emptiness is what makes architecture a major art. I do architecture because I consider it a major art even though it is influenced by other disciplines.

This vertical tower project in Ginza was built very well. In Tokyo, there are three or four companies that build very well when they want to and since this is Tokyo—the center of Tokyo—they built it exactly like I wanted, with a lot of detail. They did everything exactly, to perfection. It’s a little world of its own, the world of Ginza, and even though the building is a little bit taller than the ones next to it we think it integrates in a different way, with a unique red color on the facade and with very interesting interior spaces.

Shiseido Building, Tokyo Japan: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Shiseido Building, Tokyo Japan: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

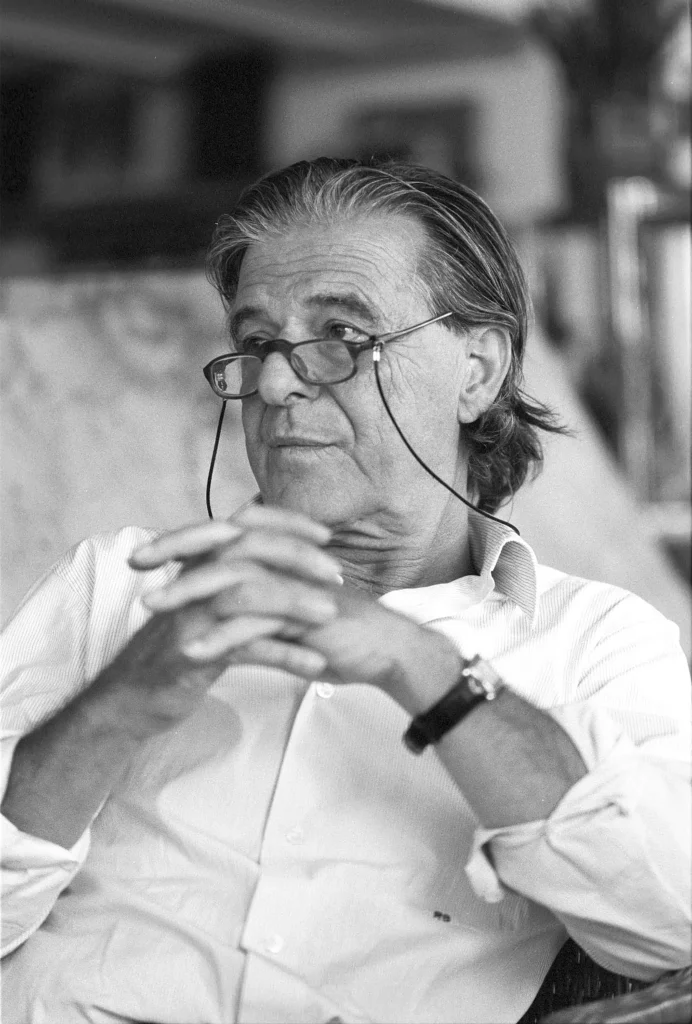

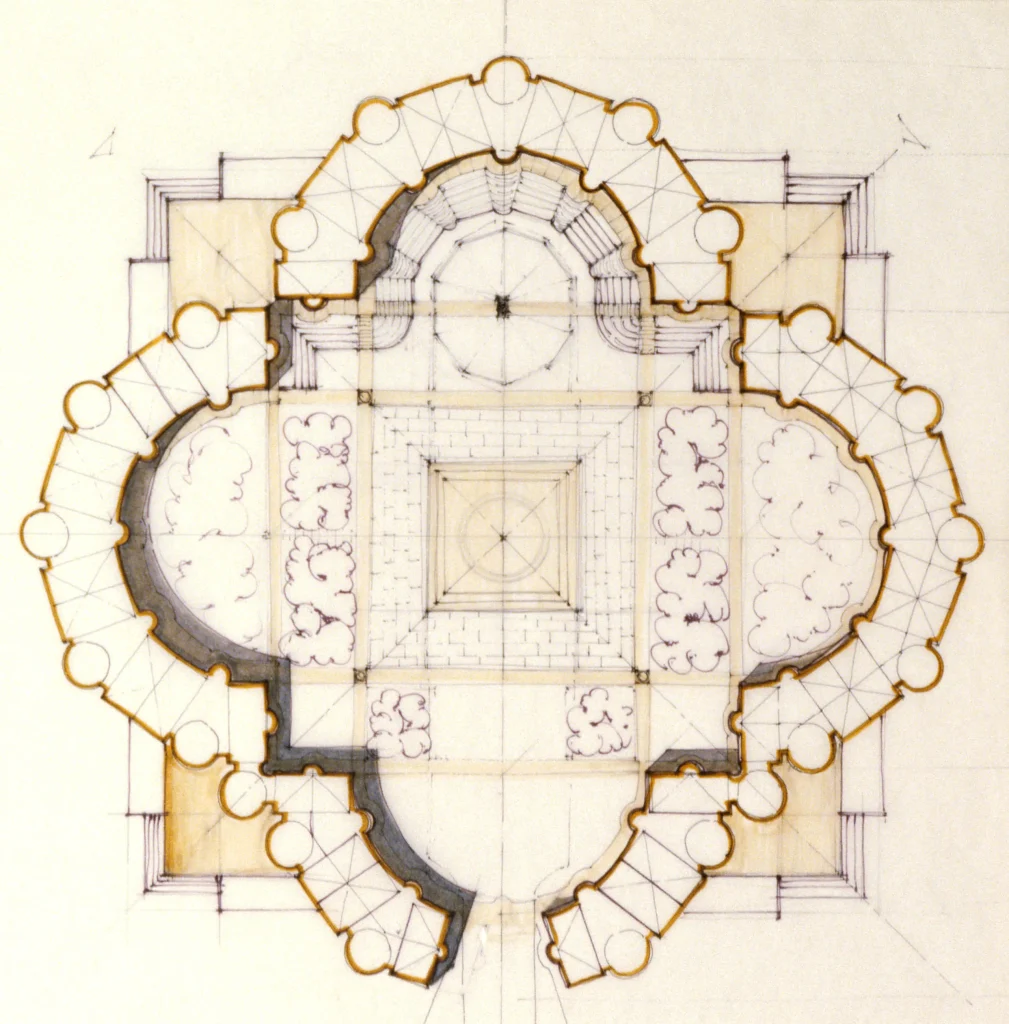

You are very interested in beauty—in creating beauty with space and in the architect’s ability to achieve it. At the same time, I think you have a great knowledge of geometry. What role does the knowledge of geometry play in achieving the beauty you talk about?Well, beauty is what we pursue as something unattainable to achieve a complete work of art. The complete work of art in architecture is like a greyhound race, where the finish line is always there at the end, but is never achieved. Beauty is, in the end, the only thing that interests me. Beauty and intelligence are the two things I like.

Geometry has been—and indeed is, in our projects—the substratum. Sometimes it is not seen or it is not apparent. For example, the Walden has a very powerful internal geometry, but it does not correspond to the façade. We make it inside the building, and it is not evident, we do not want to show it. But it is the substratum for the composition and for the definition of the interior and exterior spaces of the buildings.

Walden 7, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Walden 7, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Walden 7, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Walden 7, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Walden 7, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Do you think that perhaps in part the quality of certain architecture is due to the production of an excess of space, of creating larger places than necessary? Somehow this seems to happen in your house workshop. Is the excess of space the real luxury?

Exactly. I have a tendency towards too much space. I always tell the people I work with that luxury lies in building a slightly larger space. Luxury is not in painting the doors gold or working with an expensive material, but in making the surrounding space a little bigger. For example, Barcelona airport is a monumental space, defined by a roof that covers it. What happens is that, at the same time, in a monumental space you must provide spaces at a more humane scale. The most difficult thing in architecture is the change of scale. Even when you articulate space at an urban scale you must also think of the individual person’s scale.

La Fábrica, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Fábrica, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Fábrica, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Fábrica, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Fábrica, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

You speak of Barcelona, and of Catalonia in general, as a place that belongs to the periphery of Europe. What are the benefits of an architect working from the periphery of Catalonia or Spain, rather than from other places in Europe? It makes a difference, but it’s not that it’s advantageous. Living and working from Barcelona—from a peripheral region in Spain and Europe—gives you a different position in the world. There is no work for everyone despite being a city of architects, with suburbs that are ugly but work better than in other cities. Even in the suburbs, you can see this variety of architecture that I was talking about before, although urbanistically they are not ideal. What has Barcelona done? It has been necessary to have a different attitude, an open attitude, and an interest in other cultures, which is necessary when you are not born in the center—when you are not born in New York or Paris or Moscow or Beijing. When you are born in a small, peripheral city, you must be interested in other things and you must make an effort to get to know other cultures.

La Fábrica, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

La Fábrica, Sant Just Desvern, Barcelona Spain: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Les Echelles du Baroque, Pl. de Séoul, Paris France: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Les Echelles du Baroque, Pl. de Séoul, Paris France: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Perhaps despite the disadvantages and the extra effort, you have to make to get to know the ‘center’, this makes people look outwards with special interest. For someone from London or Washington, it is perhaps almost more complicated to be able to see beyond their own city.

And this has an impact on reality, because when London architects work—and they work out of London—they are making a London architecture and moving it somewhere else.

Exactly.

I can’t do this, though. I can’t do it because it doesn’t make any sense and it wouldn’t work. I have to be interested in the architecture of that place and from there produce another architecture. And when you are born in London, you don’t have to make this effort. This effort is a source of knowledge beyond architecture.

Going back to the projects you are developing now in cities in China—which are almost complete cities: how do you think about these projects of territorial scale so that they do not become purely utopian projects?

Every case is different, but when you go to work in China, the first thing you sign is a contract in which you lose the copyright. So, you know from the beginning that they want your ideas, but you lose all rights to them. The most important commissions we have received from China have been direct commissions from the Chinese government at a time when the government wanted to change the shape of the city.

The last Chinese government, in a meeting of the communist party 4 years ago, tried to define another model of the city. They had first done a model for the city of Shenzhen, and then they did another vertical model for the city of Shanghai, which didn’t work. And now they wanted to try a model without carbon emissions, greener, without cars, with lower buildings, even changing ownership system. We have been working together with local architects, on the one hand, and with Chinese engineers, who are very powerful. China is a construction machine, they have built a lot and very quickly, they have changed the country in 40 years, and they have learned a lot in this time. The problem is that they have no sense of space, no sense of emptiness, and no sense of individuality.

We are asked to think of the Chinese city as a mixture of a Chinese city and a European city. So, we have projected different cities incorporating urban design, public space design, something in between planning and architecture. These projects are models that they will later repeat in other places. And this is how we have worked, with many difficulties because we have to get along with planning people, with the big IT companies, and their obsessions with 5G—they believe everything will be possible with 5G. These are the models that we have put on the table and that they are now developing.

Palashevskiy Lane, Moscow Russia: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Palashevskiy Lane, Moscow Russia: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Palashevskiy Lane, Moscow Russia: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

What stage are you at?

They are in the development phase. Anyway, now with COVID-19, even in China, there has been a recession again. The history of China has always been like this, fluctuations between internationalization and protectionism. Now they have gone back to local interest. Chinese architects are very prepared, but they lack creativity because there is no individualism due to the communist system. They are copying other things, they are taking bits and pieces of projects from other places, and they are putting them together and mixing them. So, changing urbanism in China is very difficult. It’s almost a useless war because they are talking about a pending subject of the last century and of this century. We talk about energy, green, climate change, all these issues, but the final physical change of urbanism is almost a lost subject and in the end, the cities reproduce themselves as large suburbs. But large suburbs that have no identity of their own.

All Chinese cities resemble each other because they are copies of others. The subject of the city is very difficult to deal with in China, and in the end, it clashes with the administration, with all the bureaucracy. For example, when we talk about housing, and that we want to break the traditional block and make other typologies, they say yes, but then they start to say that they build better by making blocks. In short, it is a fight against a ghost that wants to renew the city, change the city, and change the urban design, but it is almost impossible.

Xiongan Wetlands, China: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

Xiongan Wetlands, China: Ricardo Bofill Taller Arquitectura

You said in an interview “that architects should dedicate themselves to changing obsolete places in the city.” Do you think there is anything currently being done in this direction?

Indeed, the city is made at a certain time, it is built in a certain area, but it has to last over time. You have to be able to change the public space, reuse it, but with a sense of conservation. You can’t take a street, like some current proposals in Paris, for example, and transform it into a greenway. And you can’t take a street and change its typology. The typology of the street is something you have to respect. Just as you respect an old building, you have to respect a street that was built a long time ago.

In a similar manner, you can’t take an old neighborhood and change the way it works. Therefore, you have to adapt the city to the present time, while respecting its history. You have to make it evolve, the way buildings evolve. Cities have to change and adapt to the new situations of climate change, energy change, energy saving. But not just in any way— not the way it is done in Barcelona, where they suddenly take a street, paint it yellow and start putting up objects so that cars can’t get through. It is not done in this elementary, primary way, destroying the typology of a street that must be preserved anyway. It can’t be done in just any way, it is a complex job, which has to be done with knowledge, with prepared people. Changing the streets in any way means destroying your own history, your own landscape, and your own identity. Therefore, you have to do it, but with serious knowledge of the meaning of a particular street or square.

2 AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

MARCELA ARAGÜEZ, PHD

Associate Program Director, IE University (Madrid, SP)

Dr. Marcela Aragüez is a Spanish architect and researcher based in Madrid and Zurich. She is Associate Director of the Bachelor in Architectural Studies at IE University in Madrid-Segovia, where she leads a Design Studio Unit. Dr. Aragüez holds a Master in Architecture from the University of Granada, and an MSc and PhD in Architectural History and Theory from the Bartlett School of Architecture UCL. Her research interests lies in the understanding of uncertainty as a spatial quality in architecture, with a particular emphasis on the investigation of post-war practices from a cross-cultural perspective. Her work has been acknowledged with grants and awards from the Japan Foundation, Sasakawa Foundation, Canon Foundation, and the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain.