To All the Misfits: The Work of Adam Nathaniel Furman

Title: To All the Misfits: The Work of Adam Nathaniel Furman

Authors: Regner Ramos

Keywords: Marcio Kogan, Adam Nathaniel Furman, Architecture, Design, Queer Architecture, Interview

1 INTRODUCTION

The work of Adam Nathaniel Furman is quite literally wonder-full. It calls to you in its loudness, and takes you back to memories rummaging through toy bins and reading through comic books. His projects, which span across scales and mediums—from ceramic knick knacks to films, from furniture to jumbo installations—scream of celebration, inviting spectators, visitors, and users alike to imagine different worlds where the formal, traditional rules of architecture are smashed, re-stacked one on top of the other and painted in super-saturated, ultra-glossy kaleidoscopic patterns. It’s no wonder Furman is not everyone’s cup of tea, and he’s okay with that. His work has been exhibited in London, Paris, New York, Milan, Rome, Eindhoven, Minneapolis, Portland, Kortrijk, Tel Aviv, Veszprem, Mumbai, Vienna and Glasgow, and is held in the collections of the Design Museum, the Sir John Soane’s Museum, the Carnegie Museum of Art, the Abet Museum, & the Architectural Association. Furman’s work has also been published widely, with a breadth of international projects, and his new book Queer Spaces: An Atlas of LGBTIA+ Places and Stories (co-edited with Joshua Mardell), has just been published by RIBA.

From my office iMac, I log into our Google Meet session, and as he ‘enters’, I hear him making noises and fiddling with his camera, which is pointed up towards the heavens, and I chuckle and say,“What a lovely ceiling!” His smile is nearly as bright as his neon orange spectacles—nearly. And as we begin our conversation—which starts with exchanges of what quarantine has been like, colonization, and our grandmothers, though maybe not in that order—, more than an interview with one of the UK’s most provocative designers, I feel like it’s a catch-up session between two people who have never met.

PHaB Chairs – Yeshen Venema

2 INTERVIEW

I thought we could start by talking about how your cultural heritage informs how you see architecture and your own work right now.

Heritage in terms of, I guess, family background?I don’t have cultural belongings that are shared with many people that I can really get a grip on easily. The effect on me has been somewhat nebulous. I think in terms of creative work I would say it’s had a positive impact, because it’s made me who I am. Growing up in London was probably the savior of myself, just because it was a city that—as you know—welcomes everybody. You’re not really judged quite so quickly in the way that you are in other places. So, I could take part in multiple subcultural communities.

I find the word ‘community’ quite problematic, though. ‘Scenes’ is probably better, where I met really amazing people. I participated in the expression of difference in manifold ways. That was amazing, as a kid who grew up with parents from very different places to where I was living, from very different backgrounds.

Is your mother from Argentina?

My father is from a small town in north Argentina, my mother was brought up in Japan. She’s half-Japanese. Her father was a refugee, escaping from the Nazis in the 1930s. He made it to Japan, where he met a lady and got her pregnant. And, they spent the war in the mountains directly north of Tokyo, which is where my mum is from and was brought up. My parents met in Israel and then they moved to London, where they had their kids.

Aesthetics are an extremely important way to preserve your identity. I saw that in my mother and my grandmother—who are people that thought they never belonged anywhere—, and I think this is quite common with a lot of immigrant families that I know.

You either preserve your identity or create an identity you’re comfortable with, because frankly you weren’t really welcome wherever you lived anyway.

So, the creation of a comparable, meaningfully different place that you own, is a way to expresses yourself—through objects, clothes, and space. It’s extremely important, particularly for my mother and my grandmother, but of course my father also participated in this, being somebody who never quite belonged. And that was passed on to me. My parents, becoming successful business people, they really wanted me to go to a good school and to speak good English—proper British English. I went to a posh public school, which in England means the opposite in America—it’s like an old-fashioned private school—and I didn’t get on. I wasn’t really welcomed by the British kids, who could be quite awful. But, it was a school in North London and there were a lot of other kids from similarly different backgrounds, Iranians, Pakistanis… You know, that’s great. You didn’t need the British kids.

That was a way of experiencing identity that—from a very early age—already related to objects, spaces, representations, things which in an academic discourse—in a traditional way—are normally considered kitsch, rubbish, superficial, all that. It was all completely not allowed. But, it was all the stuff that informed who I was. Actually, that literally made my identity and were the things that grounded me. You know, when I came out, I was bullied at school and soI embedded myself in London, especially the London queer scene, the punk scene, the cyber scene. You’re then part of a group, and that group is defined by what you wear, the things that you design, and the way you speak. It was not meaningless at all.

This was very often aligned with political views. These were places to hang out and to have fun, but they were also very embedded with an ideology. Then I went to architecture school and, oh God, all of that—everything that was meaningful to me—they were like, “No”. I remember the very first project I did, they literally humiliated me in front of the class. “This is kitsch, rubbish.” So, that pretty much defines the rest of my experience with the architecture world. Everything that was important to me, everything I valued was considered superficial and decorative, because it’s not engaging politically with real action. I sort of got lost somewhere in the middle. My background was really important for the particular way I approach design in relation to my identity, a constant construction through elements like objects.

That’s so relatable to me too. I think that what I’m like now and what I value in terms of architecture, is very much informed by my relationship with my grandmother, by my upbringing, and her particular aesthetic and how she made her home. I wrote this short essay about her house, and the other day one of my cousins read it to her which was really sweet. I think it was nice to know that she understands just how important her presence in my life is now to me as a researcher, as an architectural thinker. I’ve read in other interviews you’ve done, that you reference your childhood a lot, as a kid. YOU mentioned that you didn’t fit in, you talked about being dyslexic as well.

Are you as well?

The Democratic Monument 2

No, I have other things going on.

It’s not a problem, it’s just a way of being but it’s really common with designers. I think it’s almost more than half are dyslexic

Tell me a little bit about how the experience of you as a kid manifests in the work that you do now. And, also, how it strengths you as a designer, as an educator and a thinker. This quality of not fitting in, of having this different way of being, how do you see that now?

The kooky part of me turns to anger a lot of the time. So, first of all, yes. I don’t know if this is also something that resonates with you, but absolutely: I can look back and it’s very, very clear how I’m defined by the things that I experienced as a kid, both positively and negatively. I can it, it’s just clear as day now, especially at this age that I’m reaching. I’m able to look back.

I was very much the stereotypical kid who didn’t fit in, who takes photos and develops them in the school photo lab, or does paintings moodily on their own. And, then what I discovered was drugs. My family background was not necessarily fit to breeding a child who—in terms of mannerisms and cultural understandings—didn’t know how to fit in very easily. I guess that set me up for this kind of character where I never felt that I could ever just be comfortable in the groups that existed. And, then again, you know, I’m one of those people who just survived in school and tried to not get bullied. Which did end up happening later with the being gay thing, because it was such a big deal at the time. I would become a mirror.

Even now, I struggle with social situations. Not in a terrible way, but I avoid them as much as possible. With every person that I’m with in real life, my brain goes into hyper fast mode, wondering what they want to hear. What are they interested in? I’m just a bit of a chameleon. I go into a situation as the person who they want to be spending time with and enjoying. But, then that means I never enjoy any of the situations. I’m exhausted after them.

At the same time, it gave me great skills generally in life, and in my professional career, to be able to have many hats. Again, people ask me, “What are you?” And I’m just happy with my designer hat, I’m happy with my journalism hat, I’m happy with my writing hat. I can, sort of, change them quite easily. So, it’s been helpful being a chameleon character.

Dyslexia runs in my family, we know that now. However, even with the support I had—I learned to read and write—I was an incredibly slow learner, which was one of the many peripheral aspects of dyslexia. I got really bad grades. I felt stupid all the time. I used to compensate with being very funny in class, causing problems, but in a funny way, being a bit of a joker. But there was, you know, the savior, which was: I could draw. I became a real arty kid in order to navigate school, but it was still a difficult one with the teachers. I was drawing constantly, non-stop. It became my happy place. It was my “this is why I’m not stupid”. “This is why I can actually do this.” I think I was shit but, I didn’t feel shit. You know, like positive reinforcement, like training my dog, training her through positive reinforcement, giving her treats to do things. I just got hardwired into thinking that. And, it never stopped.

I ended up doing an art GCSE and an art A-level. I always loved architecture, and for some reason I didn’t think I could do it, but then I went to Central Saint Martins. I had a fantastic tutor at school who supported me in studying architecture because I didn’t think I was clever enough to do it. That experience made me really focused on making and drawing, just by chance, because it was something I could do. And, it made me feel good. The more you do something no matter what it is, it could be anything, but the more you do it, you get better and it, and you start being able to express yourself through it. By the time I was 18, I was a typical teenager. I didn’t work and did lots of drugs, but I had just piles of drawings, piles. A room full of drawings. That’s set me for the rest of my life.

House of Tretrarchs

I think that is really interesting, because I think queer kids grow up with such a particular experience as children and teenagers. This aspect of never really fitting in—especially during the years, you and I, were kids—is crucial, and it’s changing now, maybe?

How old are you?

I’m 35.

Oh, so you’re young then.

How old are you?

I’m going to be 38 really soon.

I think that growing up in the 80s and 90s, our experiences weren’t that dissimilar. Although there must have been a huge difference growing up in London and growing up in Puerto Rico, which was really conservative, but now I think that’s changing. But, I do think that part of the reason why I’m interested in you as a kid and me as a kid is: I wonder if this llooking back is a queer way of making sense, a queer way of thinking about architecture now. I don’t know if straight architects our age are constantly looking back the way that I constantly look back on my relationship with my grandmother and the spaces that I inhabited when I was a kid. Do you think that this introspection or this criticality might be a queer way of making?

Yeah, I guess it depends how you define queer. So, if we’re talking about homosexuals and people of different sexualities and different genders, when you’re growing up, you are, from a very early age, forced to question everything. You’re forced to try and understand what’s wrong: is it you or society? Or is it both? This happens in very little interaction as well as in larger scales. Is it life? Is it family? Is it the world outside? Everything gets questioned. And, I think that from very early on we have a third eye which is the eye outside of ourselves looking at us and looking at the world around us which makes everything reflective. It’s not the case for everyone, but this is a significant majority of gay people.

I think that means that you possibly have an extremely rich inner experience when you’re growing up; this also comes into people who suffer a lot, when they’re young, in different ways. I’m not saying it’s just us. I just know that it’s a lot of gay people that I know have also experienced this. When you get older, you continue to do that for most of your life. When you get older you gain the ability to look back and have a sort of three- dimensional view of things. I think a very good example of that aspect is shown really well in Proust’s writings and his forensic examination of the entire arch of his life, which also took in all of society in it. I also think that there’s a particular relationship with nostalgia and looking back with tenderness and love on things which normally would be considered ‘not serious’ and a bit ‘sentimental’. Which I think always has been part of gay culture. I don’t think you and me are that unusual as gay men having such close relationships with our grandmothers; it’s quite common. I do think it’s something that goes back a long way in the modernity of gay history and I think that there’s a tradition there. But, I don’t think that it’s exclusive to us. Have you read Karl Ove Knausgård?

The Liberal Archive (Proposal 2020)

No, I haven’t.

It’s been an epic of the past decade. It’s a very masculine, hetero version of the same thing: looking back on a relationship with the father and the family. So, you know it’s not an impulsive exclusive. But, I do think that necessarily the subject of our impulse towards a retrospective, reflective gaze tends to be quite different.

Earlier, when you talked about your experience coming into architecture school with this particular way of creating informed by your particular family, there is this tradition of flattening everything out so that you create this same kind of designer. I heard another interview that you’ve done and you… I’ll quote it loosely, “diversity and representation of society by making many different designers that can blow open with a nuclear bomb this little world that controls a particular aesthetic that defines what the profession is”. You said it means that people can express their own difference and that you’ve enjoyed the process of finding that throughout the years. So, I wanted to talk a little bit about this aspect of enjoyment and pleasure in the method of design itself—embracing who you are and enjoying that.

In architecture in general, there is a terrible protestant ethic of ‘you have to suffer for your work and the work must embody, in many ways, the puritanical suffering of those who’ve exercised all sin for their work’. I get the impression that with architects, they help to convey the sense that they’ve been flagellating themselves in the kitchen. I think that’s problematic because that comes up in all kinds of horrible ways in terms of architectural work culture. The way that we treat younger architects, the education system, and the way it values our drawings, embodies labour, and actually don’t embody anything apart from that. The idea that complexity is simply the embodiment of hard work is horrendous.

There’s a kind of lexus of beliefs that pushes people towards producing architecture that is about signifying. I think in architecture there’s an equivalent of virtue signaling, through the amount of embodied effort and work you put in, and also the kind of painfully pared-back nature of the work that you produce that shows that you’re part of the crowd. You’re virtue signaling through your architecture and reached the upper echelons of a very elite group of people who only allow in a particular aesthetic—and not only just an aesthetic, but also forming a lifestyle that allows you to present yourself as embodying that perspective. Whether that’s an aesthetic of doing architecture that is very socially engaged, that goes with you basically giving your life to that, not earning any money and just devoting yourself to society and the communities you’re doing the architecture for. The architecture embodies the sacrifice that you’re giving. Equally, it happens if you’re doing minimalism, which requires endless amounts of difficult work for a result that is literally not noticeable. So pleasure is exercised from us from very early on. And it’s not just pleasure, it’s also difference. Literally anybody who wants to embody themselves in any way that’s not part of the norm, you cannot proceed past architecture school. If you manage to get to do that through your own work at school, it would be amazing. It’s more possible nowadays. You definitely can’t practice that way. First of all, there’s the professional barriers and then there’s the barriers of planning which are set against you. The pleasure of being able to represent anything to do with you is exercised. But, that’s also true of any form of pleasure—even just having a normal life and having a normal experience of working with a good work-life balance is taken out as well. And, the amount of labour that goes into unnecessary work that you’re training to go through to produce all of the buildings is also completely about enjoyment. I don’t really understand why architecture has this, sort of, Jesus complex.

Nagatacho 2 – Jan Vranovsky

Yeah, you’re right. It’s almost like you can only speak of somebody deriving pleasure from architecture once the building is completed and it’s for somebody else. But, the process itself should not embody that at all, and it’s this idea of oobjectivity

Pleasure is allowed but it’s a very specific type of pleasure, which is equivalent to the pleasure of an art critic who has been training for many years to understand the corners of art theory—to be able to look at a black square on a wall, understand it, and appreciate it because they have been culturized, encultured, indoctrinated into a group who can understand that something is meant to be enjoyed in a particular way. It’s a little bit like an in-joke in a movie or a play which is aimed at those who have only read something else which most people haven’t read. This pleasure of knowing that this is so wonderfully funny, most of the other people won’t know it but, you know it. We get it. It’s all about exclusion. It’s the pleasure of exclusion, specifically it’s a form of elitism that is present throughout cultural life.

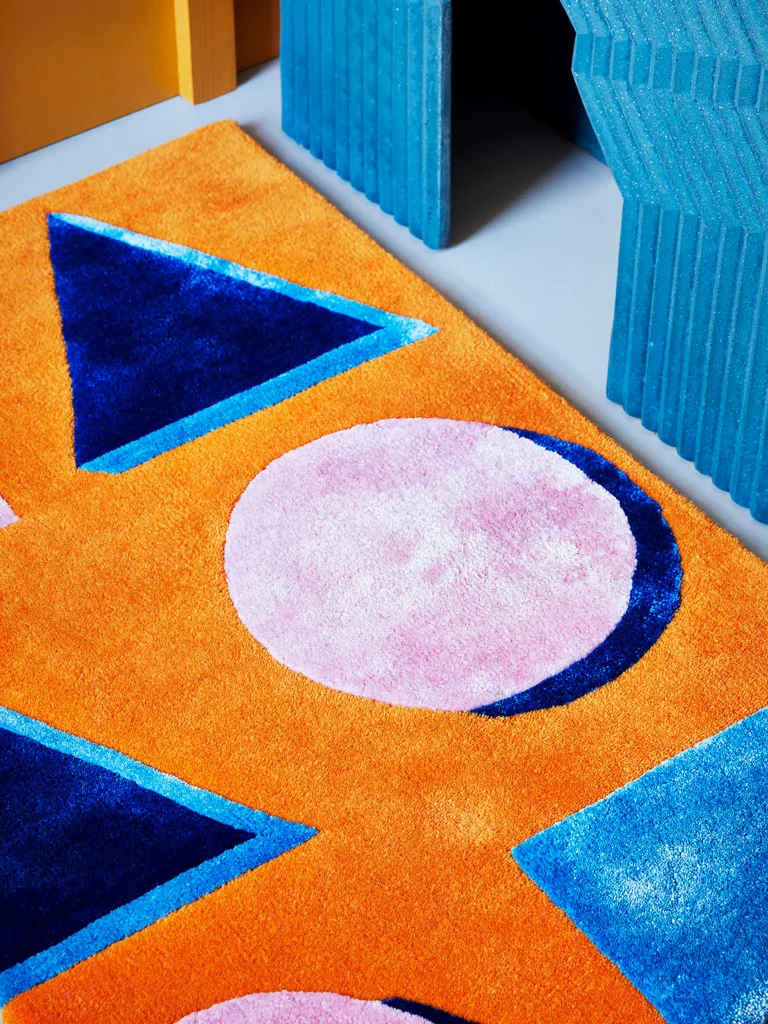

Mediterranean – John Day

And, your work I think disrupts that because it plays around with iconography and color and it plays around with scale and wonder. Often, the strange thing is that that is discouraged because suddenly it is appealing to people who don’t need to understand a bunch of things to be able to like and gravitate towards it. It’s understandable in a way, or it reminds them of something else and that’s why they like it, or it would just look beautiful in their home. Do you feel architecture, as a discipline, likes to differentiate itself from art, even if they converge in your work? Art has a lot of the same problems, very similar. They are in no way better. I think that in architecture there’s a celebration of the community in a sense that they do engagement where they say, ‘Ok we’re doing a project in this particular area where there’s community, and we have to create something where the members don’t necessarily need to be encultured to appreciate it’. It would be great if that happened more. I guess what I talk about is slightly different.

I argue for the dismantlement of the elite political aesthetic projects of architecture and art. I imagine that a parliament of aesthetics could arise—where things that are normally kept at the nightclubs, or the living rooms, or the studios with designers who never managed to do anything at a certain scale, or architects who are excluded because what they do is very different—to allow them to participate in the public realm, in the public sector, in places where their presence will be felt and understood. The hegemony or monopoly of aesthetic in public realms and an infatuation of content is traditionalist.

The Democratic Monument

Do you see your work as being a disruptor or an agitator? Or is there a difference between those words at all?

You know, somebody asked me, I think last year, “Why are you so antagonistic?” Is that good? I guess I think that throughout your life and your career you have to be on the defensive the whole time, constantly. I get pretty constant attacks and I’ve sort of taken off, I’ve sort of run away now. I’m too old for it. It puts you in a mode where you are going to inevitably react to that. Especially if you’re someone like me who’s like, “Well, fuck you”, you know. So, in many ways, unfortunately, I am a product of a context which was or has been somewhat confronted. A lot of the work does, in many ways, exist in that environment and was controversial. It was not antagonistic, but provocative. I came specifically from an angle that was: time to show what I care about. Literally, the things that look pretty. So yes, I’m trying to move away from that because I’m very rarely on social media anymore really, I very rarely do stuff like that now compared to before. Also after some pretty unpleasant experiences last year, where things were weaponized against me in public. I’ve just taken a step back. I would like to just re-engage positively with the things that I care about and try and separate myself from the perpetually angry people who are my age or younger even now.It’s not just old people necessarily, who I’ve had to react against in the past.

Superfice 03 – Delfino Sisto Legnani & Marco Cappelletti

3 AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

REGNER RAMOS

Dr. Regner Ramos holds a Masters in Architecture from the University of Puerto Rico School of Architecture and a PhD in Architecture from the Bartlett School of Architecture UCL. He has taught at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, London College of Communication, University of Hertfordshire, and Queen Mary University of London. Dr. Ramos is a tenure-track Associate Professor at the UPR School of Architecture, where he teaches architectural design, architectural theory, magazine production, and supervises M.Arch dissertations. He is the architecture Editor at Glass magazine, and with Dr. Sharif Mowlabocus, co-editor of Queer Sites in Global Contexts: Technologies, Spaces, and Otherness (Routledge, 2021). His research focuses on the relationship between queer identity, internet technologies, and the built environment, exploring these relations via architectural mediums such as model-making, architectural drawings, site-based performances and events, and through print and digital publishing. His latest research project is called “Cüirtopia”, and his work has been shown internationally—most recently at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.